U.S. Department of Labor’s Proposed Rules Focus on Independent Contractor Status

Quick Links:

Whether real estate professionals are categorized as independent contractors or employees of the brokerage firms with which they affiliate has long been an issue of concern. The law in Illinois remains positive for supporting independent contractor relationships. Nevertheless, when it comes to litigation as to whether a real estate licensee is truly an independent contractor remains a multifactor inquiry.

Research and analysis by Lisa Harms Hartzler,

Sorling Northrup Attorneys

The U.S. Department of Labor asserts that the various factors used to determine the outcome of such lawsuits around the country can be inconsistently applied because there is little direction as to which factors matter most and why. It recently issued a Notice of Proposed Rule Making under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) in an attempt to promote certainty, reduce litigation, and encourage innovation in the economy.

This article will explore the proposed rules, summarize existing law in Illinois, and provide guidance on structuring an independent contractor relationship between a brokerage firm and a real estate licensee. It will also touch briefly on new guidance from the Equal Opportunity Commission for employers in the Covid-19 era.

The Need for New Rules under the FSLA

The FLSA requires employers to pay employees the federal minimum wage for every hour worked, to pay overtime for every hour worked over a 40-hour workweek, and to keep certain records. Other statutes governing employer-provided benefits (such as health insurance, retirement contributions, and paid time-off) and tax liabilities (including Social Security, Medicare, unemployment insurance, and workers’ compensation) also turn on the distinction between employees and independent contractors. The FLSA and other statutes only apply to employees, not to independent contractors. Consequently, making a clear distinction between the two relationships is important.

Under the common law, employment versus independent contractor status turns on traditional agency principles—a hiring person’s right to control the manner and means by which a worker accomplishes tasks. Congress codified these concepts as applicable to the National Labor Relations Act and the Social Security Act. It has not done so for the FLSA. Since 1992, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that the FLSA is broader than the common law. Although obviously not meant to stamp all workers as employees, the Department of Labor contends that this “broader” standard remains uncertain.

The FLSA defines “to employ” as meaning “to suffer or permit to work.” Courts and the Department of Labor have long interpreted this definition to require an evaluation of the extent of the worker’s economic dependence on the alleged employer by applying a multifactor test looking at the economic reality of the situation. According to the Department, the multifactor evaluation has led to uncertainty because there is no guidance as to what factors matter most and why, the factors have been applied inconsistently, and the lines between the factors have become blurred.

In an effort to address these shortcomings, the Department of Labor (DOL) issued proposed new rules. It is uncertain how long it may take the DOL to evaluate comments and issue final rules or even whether they will be issued if a different administration is installed after the November election. Nevertheless, the proposed rules do attempt to codify existing jurisprudence and the Department’s own interpretations and are worth examining.

The Proposed Rules

The DOL hopes to clarify in the proposed rules the difference between an employee, who is economically dependent on the employer, and an independent contractor, who is in business for him- or herself. It suggests five factors to be applied in the economic reality test. The first two are “core factors,” and are be given the most weight:

- The nature and degree of the worker’s control over the work.

- The worker’s opportunity for profit and loss based on initiative or management of the worker’s own investment.

- The skill required in performing the work.

- The permanence of the working relationship.

- The integration of the worker’s performance into the business unit to which the worker provides service.

The ability to control one’s work strikes at the core of what it means to be an entrepreneurial independent contractor, as opposed to a “wage earner” employee. For example, an individual’s substantial control includes setting his or her own work schedule, choosing assignments, working with little or no supervision (using broad discretion and business judgment), and being able to work for others, including a potential employer’s competitors.

Requiring an individual to comply with specific legal obligations, satisfy health and safety standards, carry insurance, meet contractually agreed-upon deadlines or quality control standards, or satisfy other similar terms that are typical of contractual relationships between businesses (as opposed to employment relationships) does not constitute control that makes the individual more or less likely to be an employee under the FLSA.

The second core factor, the opportunity to earn profits and risk losses, is similarly important to a finding of independent contractor status. Personal financial investment is frequently considered a meaningful means to satisfy this factor but it is not the only way. Individuals who “invest little” may nonetheless have an opportunity for profit through the exercise of personal initiative. Under the proposed rules, this combined factor would weigh towards an individual being classified as an independent contractor if he or she has an opportunity for profit or loss based on either or both: (1) the exercise of personal initiative, including managerial skill or business acumen; and/or (2) the management of investments in, or capital expenditure on, for example, helpers, equipment, or material.

The three other less important factors are to be applied as appropriate if the two core factors are not determinative. The “skill required” factor weighs in favor of classification as an independent contractor where the work at issue requires specialized training or skill that the potential employer does not provide. The permanence factor would weigh in favor of an individual being classified as an independent contractor where his or her working relationship with the potential employer is by design definite in duration or sporadic. In contrast, the factor would weigh in favor of classification as an employee where the individual and the potential employer have a working relationship that is by design indefinite in duration or continuous.

Finally, the word “integral” in the last factor does not mean “very important” under the proposed rules. In this factor, being integral to a business unit is more analogous to an individual in a production line. This factor would weigh in favor of employee status where a worker is a component of a potential employer’s integrated production process, whether for goods or services as, for example, a programmer who works on a software development team. In contrast, an individual service provider who is able to perform his or her duties without depending on the potential employer’s production process would more likely be considered an independent contractor.

In summary, the DOL believes the two core factors to be most important and typically determinant of a worker’s status. The other factors can be relevant in appropriate circumstances but are de-emphasized in the proposed rules. This approach is probably the biggest departure from case law and the DOL’s own prior opinions. In the end, the proposed rules also conclude that actual practice of the parties involved—both of the worker (or workers) at issue and of the potential employer—is more relevant than what may be contractually or theoretically possible.

Illinois Law Remains Steady

While independent contractor status may be inconsistently determined under the FLSA, the law in Illinois, at least with respect to real estate professionals, remains much clearer. The Illinois Real Estate License Act continues to recognize that a licensee may practice the real estate profession as independent contractor under a written agreement with a brokerage. The Illinois Workers Compensation Act and the Unemployment Insurance Act specifically exclude real estate professionals paid by commission from being deemed employees. No recently reported court decisions have considered the classification of a licensee. The traditional practice of real estate professionals doing business as independent contractors of brokers remains legitimate in Illinois.

Nevertheless, classifying a worker as an employee or an independent contractor whenever litigation arises is still a highly fact-specific inquiry. Courts in cases have applied various factors under the common law, noting that no single factor would decide the outcome. In a 2018 non-real estate licensee case, an Illinois appellate court considered whether the alleged employer: (1) could control the manner in which the worker performed; (2) dictated the worker’s schedule; (3) paid the worker by the hour; (4) withheld income and social security taxes from the worker’s compensation; (5) could discharge the person at will; and (6) supplied the worker with material and equipment.

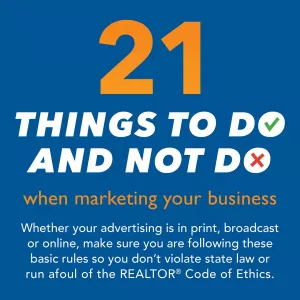

As you can see, these factors are substantially different from those described by the proposed rules under the FLSA. In general, however, they are just a different way of expressing similar concepts. The bottom line is that when an independent contractor relationship is desired between a brokerage and a licensee, there should be a written contract that incorporates as many of these general concepts as possible:

- Payments should be commission-based for sales, not hours worked (providing an opportunity for profit based on initiative and management).

- Mandatory broker office-based work should be kept to a minimum (reducing broker control).

- Licensees should file their own tax returns and pay their own taxes.

- Licensees should be responsible for acquiring their own “tools of the trade” and bear their own expenses of doing business.

- Licensees should be free to use their own methods of doing business (subject to relevant professional regulatory and ethical rules).

- There should be a defined termination mechanism within the written agreement, typically a termination upon notice clause (a notice clause distinguishes a contractor from an at-will employee who is free to quit at any time without notice).

The more of these items included in the written contract and actually followed in practice, the more likely the licensee will be deemed to be an independent contractor. For your information, a model sponsoring broker-sponsored licensee contract can be found under the Legal tab of the Illinois REALTORS® website. As with any form, it should be reviewed with the broker’s legal counsel for modification as necessary to meet the unique aspects of the broker’s business.

Covid-19 Updates and Resources from EEOC

Brokers who do have employees may be interested in resources provided by The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The EEOC enforces workplace anti-discrimination laws applicable to employers, such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Rehabilitation Act, which applies to private employers with 15 or more employees, requires reasonable accommodation and non-discrimination based on disability, and contains rules about employer medical examinations and inquiries. EEOC has updated its information relative to permissible actions in the age of Covid 19. Recent updates include:

- Employers can require any employee to take a Covid 19 test before entering the workplace. Such a test is considered “job-related and consistent with business necessity” because the virus poses a direct threat to the health of others. An employer can bar from the workplace an employee who refuses to take a test. Teleworking employees cannot be required to be tested.

- Employers can ask employees entering the workplace if they are experiencing symptoms consistent with Covid 19 and can perform temperature checks. Individual employees may be singled out for testing or questions, but only with a good reason, such as the employee looks sick or has a known family member with Covid 19.

- Employers may not ask an employee whether a family member has Covid 19 but they may ask whether an employee has been in contact with anyone who has Covid 19 or its symptoms.

- Medical information about employees must be kept confidential; however, when an employee has Covid 19 or its symptoms, an employer may notify appropriate people within the company in order to take measures to keep the workplace safe.

- An employee who knows that another co-worker is showing Covid 19 symptoms may report this information to a supervisor.

- An employer may ask an employee returning to work regarding reasonable accommodations needed.

- An employee’s request for telework does not need to be granted as a reasonable accommodation if physical presence is necessary and safety precautions are instituted to allow the employee to perform the job.

- An employer may not lay off or furlough an employee for contracting Covid 19. The Emergency Paid Sick Leave Act requires employers to provide 10 days of paid sick leave.

The EEOC website contains numerous resources, including Frequently Asked Questions and Guidelines and technical assistance questions and answers.

About the writer: Lisa Harms Hartzler is Of Counsel at Sorling Northrup Attorneys in Springfield. She graduated from the American University Washington College of Law in 1978 and began her legal career in Chicago. She has provided legal support for the Illinois REALTORS’ local governmental affairs program since she joined Sorling in 2006 and focuses her practice on municipal law, general corporate issues, not-for-profit health care law, and litigation support.

Create professional development programs that help REALTORS® strengthen their businesses.

Create professional development programs that help REALTORS® strengthen their businesses.

Protect private property rights and promote the value of REALTORS®.

Protect private property rights and promote the value of REALTORS®.

Advance ethics enforcement programs that increase REALTOR® professionalism.

Advance ethics enforcement programs that increase REALTOR® professionalism.

Protect REALTORS® by providing legal guidance and education.

Protect REALTORS® by providing legal guidance and education. Stay current on industry issues with daily news from Illinois REALTORS®, network with other professionals, attend a seminar, and keep up with industry trends through events throughout the year.

Stay current on industry issues with daily news from Illinois REALTORS®, network with other professionals, attend a seminar, and keep up with industry trends through events throughout the year.